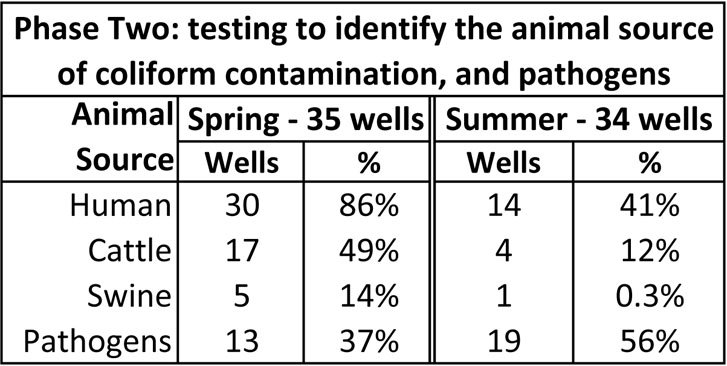

SOUTHWEST WISCONSIN - The Southwest Wisconsin Groundwater and Geology study (SWIGG) is now half way through its second of three phases. The study will be wrapped up in 2020. The current phase consists of four seasonal samplings of a small group of wells found to be contaminated with nitrate or coliform bacteria in phase one. The number of wells tested in the spring sampling was 35. In the summer sampling, it was 34.

The phase two test is very expensive and much more elaborate than the phase one test. It is designed to show which species - humans, cattle or swine - is the source of bacteria and pathogens found in the samples. Phase two testing does not identify the source of nitrate contamination.

In the spring sampling, contamination from a fecal source was observed in 32 of 35 wells (91 percent). Contamination from human fecal matter was found in 30 of 35 wells (86 percent); from cattle fecal matter in 17 of 35 wells (49 percent); and from swine fecal matter in 5 of 35 wells (14 percent). Pathogens capable of causing illness, such as Salmonella or Cryptosporidium, were found in 13 of 35 wells (37 percent).

In the summer sampling, contamination from a fecal source was observed in 25 of 34 wells (74 percent). Contamination from human fecal matter was found in 14 of 34 wells (41 percent) – two of these wells also contained fecal material from cattle; from cattle fecal matter in 4 of 34 wells (12 percent); and from swine fecal matter in 1 of 34 wells (0.3 percent). Pathogens, such as Salmonella or Cryptosporidium, capable of causing illness were found in 19 of 34 wells (56 percent).

Researchers are conducting the seasonal rounds of sampling, according to State Geologist Ken Bradbury, because they expect that the hydrogeologic system might be behaving differently in different seasons, and they hypothesize what these variations might be, but don't have preconceived ideas of what to expect.

“We don't necessarily expect to see seasonal fluctuations in the levels of contamination from different species,” Bradbury explained. “If we did see that (in a statistically significant way), it would be very interesting.”

There are some known seasonal variations in agricultural practices and land use that could have an impact. For instance, there is much less manure spreading on frozen ground in the winter or on plantings of corn and soybeans during the summer or early autumn. Water systems are also, generally, less biologically active in the colder months of the year and bacteria will typically die. Fertilizers are typically applied to crops in the spring.

Two more rounds of microbial source testing will take place to wrap up the second phase of the study. A fall sampling has already been taken in November, and the final winter sampling will be taken in January or February.

Nitrate is persistent

According to the Wisconsin Groundwater Coordinating Council’s 2019 report to the Legislature, “Nitrate is Wisconsin’s most wide-spread groundwater contaminant and is increasing in extent and severity. Nitrate levels in groundwater above two ppm indicate a source of contamination such as agricultural or turf fertilizers, animal waste, septic systems and wastewater… Approximately 90 percent of total nitrate inputs into the state’s groundwater originate from agricultural sources.”

According to Dr. Mark Borchardt who led the study of groundwater in Kewaunee County and is advising the SWIGG Study, there is no test considered scientifically reliable to determine the source of nitrate contamination of drinking water.

Unlike bacterial contamination, nitrate levels remain relatively steady and do not fluctuate seasonally. Coliform bacteria themselves are not necessarily dangerous to health unless they are the E.coli variety, but can be an indication that there is a pathway into the well water allowing infiltration of nutrients and pathogens carried in human or animal waste from around the well.

Nitrate, on the other hand, is a known health threat to women of childbearing age and children less than three years of age, above the 10 ppm safe drinking water standard level. It is also increasingly believed to offer threats to human and animal health below that level, and is believed to be implicated in some forms of cancer.

The third phase of the SWIGG Study will shine some light on the correlations between certain agricultural practices, or certain proximities of agricultural fields, manure storage lagoons and agricultural fields and well contamination. These factors can be statistically linked with higher levels of bacteria or nitrate.

“We have data on prevalence of nitrate contamination from the first phase of the study; in November 2018, 16 percent of the 301 wells tested were over 10 ppm, and in April 2019 15 percent of the 539 wells tested were over 10 ppm,” Iowa County Conservationist Katie Abbott explained. “Nitrate will come back into this study when researchers start the analysis of factors possibly correlated to contamination, such as well construction, depth to bedrock, and land use. They will look at nitrate separately from bacteria for that analysis.”

Three phases of study

The study will take place in three phases. The first, which provided some strong clues to overall well contamination across the three counties, conducted basic testing on a total of 840 wells. The basic test shows contamination from either coliform bacteria or nitrate.

The second round of testing drew from the wells that showed contamination in the first basic round of testing. It does not provide an overall idea of percentages of contamination across the three county area. Nor do the results of the seasonal microbial testing identify the source of any nitrate contamination.

The third round will look at well construction characteristics, hydrogeology around the wells tested, land use around the wells tested, and proximity to manure storage lagoons, agricultural fields where manure or agricultural chemicals are used, and septic systems. This phase will shed light on statistical correlations between these factors and well water contamination.

First phase of testing

The first phase of testing in the SWIGG Study em-ployed a much less expen-sive and technically difficult testing method. Well own-ers who participated received information about levels of coliform bacteria and nitrate in their wells.

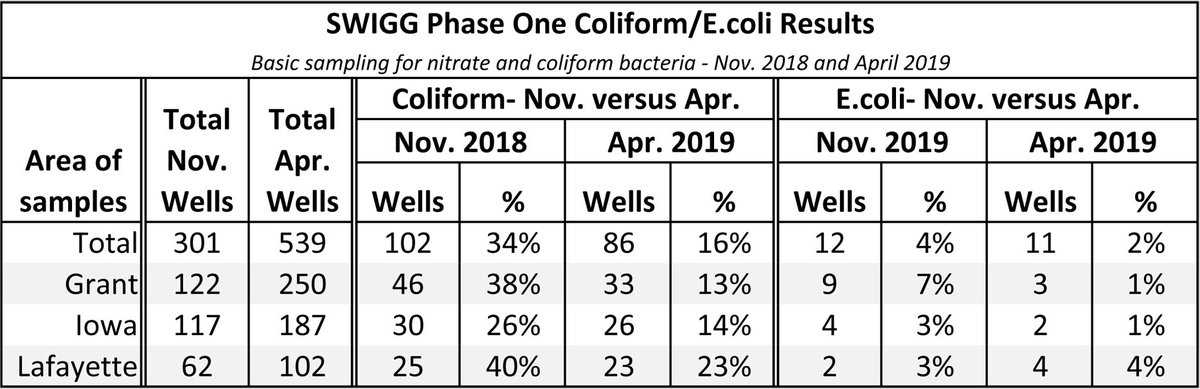

The two initial rounds of basic testing were conducted in November of 2018 and April of 2019. 301 wells were tested in November and 539 in April.

The November 2018 re-sults were released in Janu-ary of 2019. Those results showed that 42 percent of the randomly selected wells exceeded federal health standards for coliform, E.coli or nitrates.

Overall, 27 percent of the 539 wells tested in April of 2019, did not meet health standards for total coliform, E. coli, or nitrate. This is less than the 42 percent that tested positive in November 2018.

Numbers for nitrate contamination held steady across the two tests, with 16 percent in November 2018 and 15 percent in April 2019. Numbers for wells contaminated with coliform bacteria or E.coli, however, showed a dramatic difference between the two testings. Coliform was detected in 34 percent of tested wells in November, and 16 percent in April. E.coli was detected in four percent of tested wells in November and two percent in April.

Third phase of study

Greater clarity about the cause for well water contamination will be generated in the third and final phase of the study in 2020. The research team, which consists of staff from the U.S. Geological Survey and Wisconsin Geological and Natural History Survey (GNHS) at UW-Extension, will also look for correlations between water quality, geology, land use practices, and well construction.

“We just never studied the hydrology in that part of the state in detail,” noted Ken Bradbury, Director and Wisconsin State Geologist for GNHS at UW Exten-sion. Bradbury is currently creating new geologic maps for the three counties. Bradbury noted that while some areas that were heavy into mining, such as Shullsburg and Platteville, have extensive historic geologic maps from those ‘badger’ days, the hydrogeology of much of the region has not been well documented.

Well construction characteristics can govern the susceptibility to contamination. Although not mandated by the current Wisconsin well code, it is recommended that water wells be cased (a steel casing pipe cemented into the well) to below the water table. Otherwise, an uncased hole provides a direct conduit for potentially contaminated water to move from near the land surface into the well and into the area’s deep aquifers.

Preliminary work in Grant County supported by GNHS prior to the SWIGG study determined that out of 2,199 wells studied, 912, or 41 percent, have static water levels below the casing and would be classified as ‘vulnerable’ based on construction alone. The SWIGG study will provide the water quality tests to compare to well construction practices in the three counties, so the link between the two can be established.

Bedrock and soil

Grant, Iowa and Lafayette Counties are in the Driftless Area of southwest Wisconsin. Unlike Kewaunee and other counties in eastern Wisconsin, the three counties in the study were never covered by glaciers. Because of this, the landscape is much older than the glacially-modified landscapes found in other parts of the state.

The uppermost bedrock in the three counties is mostly dolomite and limestone of the Ordovician-age Sinnipee and Prairie du Chien groups. These carbonate rocks contain fractures and karst features such as sinkholes, springs, seeps, and small caves. Generally in the three counties, these rocks are within 50 feet of the surface, qualifying as shallow soil-to-bedrock areas.

Much of the uplands in the three counties are covered with a silty-clay material known as the Rountree Formation, named after exposures along Rountree Creek in the city of Platteville. This soil type is a mix of weathered carbonate bedrock and loess or windblown silt deposited during the Pleistocene age. Over the three counties, the thickness of this soil layer ranges from absent to several feet thick.

Groundwater can occur in any of the rock formations in the three counties, depending on the elevation of the water table. All of these sandstone layers form interconnected aquifers. Deep wells in this area receive most of their water from the Cambrian sandstone aquifer, but locally shallower wells are finished in the rocks of the Sinnipe or Prairie du Chien groups or in the St. Peter Sandstone. Along major river valleys sand-and-gravel aquifers supply water to wells.

Carbonate bedrock aquifers are vulnerable to contamination because water is transported quickly through bedrock fractures. Given the bedrock’s limited ability to filter contaminants, the soil overlying the bedrock and the plant root layer of the soil or ‘rhizozome’ is essential for removing contaminants prior to them reaching groundwater. Bare ground after harvest, without a vegetative cover such as is provided by plantings of cover crops exacerbates this situation.