TAINTER CREEK WATERSHED - In a gala event, more than 50 members of the Tainter Creek Watershed Council, along with friends and supporters, gathered at the Kickapoo Creekside Restaurant in Readstown last week to celebrate successful completion of a three-year grazing project in the watershed. Participants enjoyed fellowship, live music and a great meal.

The project was overseen by the Wallace Center Pasture Project, with $1.15 million in funding from the U.S. EPA Gulf of Mexico Division Farmer to Farmer Program. The funding was made available from EPA to study what positive effects increased adoption of managed intentional grazing in a watershed could have on water quality.

Ultimately, EPA’s goal is to reduce nutrient loading in the upper reaches of the Mississippi River Basin to reduce the hypoxic or ‘dead zone’ in the Gulf of Mexico.

“The Wallace Center Pasture Project used the funding in the Upper Midwest, in Indiana, Illinois and the Tainter Creek Watershed to make the connection between increased adoption of regenerative agricultural practices, water quality, and reduction of the hypoxic zone in the Gulf of Mexico,” Wallace Center’s Elisabeth Spratt explained. “The Tainter Creek project was the furthest to the north project funded through this program by EPA.”

Spratt said that going into the project back in 2019, goals included reduction of phosphorous and sediment leaving farm fields in the watershed by five percent. This meant the goal was to prevent 1,700 pounds of phosphorous, and 940 tons of sediment, from leaving farm fields in the watershed each year.

Spratt explained that at the front end, the Wallace Center estimated that to achieve these goals would require either conversion of 550 acres of cropland from row crops to managed grazing or installation of 2,500 acres of grazed cover crops.

Implementation

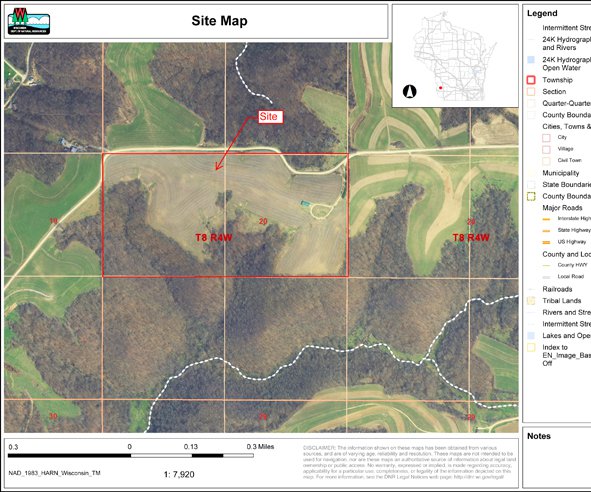

Locally, the program was implemented by Valley Stewardship Network (VSN), with technical support from two experienced local grazers – Jim Munsch of Coon Valley and Dennis Rooney of Steuben. VSN employees Dani Heisler and Monique Hassman worked extensively on the program, coordinating with farmer participants and Munsch and Rooney, creating maps to support the project, and more.

Funds from the project, described by some as ‘EQIP-Light,’ were made available to farmers to pay for:

• new permanent perimeter fencing

• replacing old perimeter fencing

• temporary fencing

• water systems and pads

• grazable seed

• agronomy equipment rental and services

• livestock equipment rental

Actual projects undertaken on watershed council farms include grazing cover crops, conversion of row crop land to managed grazing, repair of flood-damaged fencing, grazing of prairie seed plantings, repair of heavy use areas, decreasing of paddock sizes, and adding water tanks and a pipeline.

Education events

In addition to providing funding and technical assistance, the project held a series of educational events designed to help farmers understand the benefits for their farm bottom lines and stream water quality that can result from managed intentional grazing.

Those events included a fencing and grazing economics workshop held at the farm of Jeremy and Jessie Nagel, and an overview of the economics and opportunities of grassfed beef farming with Rod Ofte and Jim Munsch of the Wisconsin Grassfed Beef Cooperative. Pasture walks to view current or planned projects in the watershed took place at the farms of Jeff Ostrem and Rob and Gail Klinkner.

An event of the Coon Creek Community Watershed Council, held at the farm of Jim Munsch, detailed the tools developed by Grassland 2.0 to help measure the economic and ecological benefits of grazing.

Farmers can be proud

“The farmers of the Tainter Creek Watershed can be very proud of what they have accomplished through participating in this project and being willing to make changes on some of their working land,” Heisler said. “Along the way, there were many challenges that sometimes seemed like we were trying to build the plane while flying it, but the success we’re celebrating tonight makes all of that worthwhile.”

Heisler said that between July of 2019 and July of 2022, VSN had received 26 applications from farmers in the Tainter Creek Watershed to participate in the program. She said that in the course of initial investigatory work they found that not every applicant found the program a good fit for them, and others began the process and came out of it with a plan they can implement in the future.

In all, a total of 10 projects were implemented in the watershed, with four additional farms having achieved creation of a grazing plan for their farm. Total funding spent in the watershed on the various practices funded by the project was $173,000, and the project was implemented on a total of 986 acres in the watershed. Through the project, a total of 1,640 acres in the watershed came out of the project with a grazing plan.

“We blew our initial goals out of the water with this project, and it has been a wild success,” Heisler told the group. “Through this project in the Tainter Creek Watershed, we achieved 135 percent of our goal for reduction of phosphorous leaving fields in the watershed, and 170 percent of our goal for reduction of sediment leaving fields in the watershed.”

Heisler said this meant that phosphorous leaving farm fields in the watershed each year is reduced by 2,300 pounds (initial goal was 1,700 pounds). Reduction of sediment leaving fields in the watershed each year as a result of the project is reduced by an estimated 1,600 tons (initial goal was 940 tons).

“This project was a great success,” Spratt told the group. “Now, the Wallace Center Pasture Project can use the results of this project on a national basis to promote the positive benefits of regenerative agricultural practices.”

Tainter Creek Watershed farmer Chuck Bolstad shared in the celebration of success.

“I’m proud of what the Tainter Creek Watershed Council has been able to accomplish since we first came together in 2017,” Bolstad said. “We’ve come a long way since that first meeting attended by Grant Rudrud, Jeff Ostrem, Bruce and Sue Ristow, Berent and Luther Froiland, and my wife Karen and I. And we couldn’t have done it without all the support from Vernon County, VSN and the Wallace Center Pasture Project.”

Jim Munsch summarized the role he and Dennis Rooney played in the successful project.

“Two grazers, each with 30-40 years of experience, had a great time with two women – Dani and Monique – telling us what we had to do,” Munsch said laughing.

“We blew our initial goals out of the water with this project, and it has been a wild success,” Heisler told the group. “Through this project in the Tainter Creek Watershed, we achieved 135 percent of our goal for reduction of phosphorous leaving fields in the watershed, and 170 percent of our goal for reduction of sediment leaving fields in the watershed.”

Heisler said this meant that phosphorous leaving farm fields in the watershed each year is reduced by 2,300 pounds (initial goal was 1,700 pounds). Reduction of sediment leaving fields in the watershed each year as a result of the project is reduced by an estimated 1,600 tons (initial goal was 940 tons).

“This project was a great success,” Spratt told the group. “Now, the Wallace Center Pasture Project can use the results of this project on a national basis to promote the positive benefits of regenerative agricultural practices.”

Tainter Creek Watershed farmer Chuck Bolstad shared in the celebration of success.

“I’m proud of what the Tainter Creek Watershed Council has been able to accomplish since we first came together in 2017,” Bolstad said. “We’ve come a long way since that first meeting attended by Grant Rudrud, Jeff Ostrem, Bruce and Sue Ristow, Berent and Luther Froiland, and my wife Karen and I. And we couldn’t have done it without all the support from Vernon County, VSN and the Wallace Center Pasture Project.”

Jim Munsch summarized the role he and Dennis Rooney played in the successful project.

“Two grazers, each with 30-40 years of experience, had a great time with two women – Dani and Monique – telling us what we had to do,” Munsch said laughing.

Measuring success

A major part of the reason that the Tainter Creek Watershed was selected as the location for this project was because of the long-term water quality monitoring efforts by VSN in the watershed. This provided a baseline picture of water quality in Tainter Creek to compare to measurements taken after implementation of the grazing projects.

“We kicked off the project in July of 2019, but in reality most of the projects weren’t implemented until the 2021 and 2022 growing seasons,” Heisler pointed out. “So for purposes of measuring the impacts of the project on water quality, we won’t start to count the actual measurements until 2021.”

Heisler explained that the 2019 and 2020 water quality measurements will be considered to be ‘pre-implementation period measurements.’ She said that drought or near-drought conditions in the watershed in 2022 had complicated measurements, and caused the group to adopt a ‘chasing rainstorms’ approach to measuring water quality.

Nevertheless, initial measurements indicate that water quality in Tainter Creek appears to be improving as compared to the ‘control’ watershed, Halls Branch Creek. Halls Branch Creek was selected as a nearby, very similar watershed to Tainter Creek. In Halls Branch Creek Watershed, there is no watershed council operating, and so it is considered to represent what a local watershed would be like without conservation interventions such as have been implemented in the Tainter Creek Watershed.

“We also have to acknowledge that lots of other good work has been implemented in the watershed that didn’t result from this project,” Heisler said. “That includes other initiatives by the watershed council such as increasing acres planted in cover crops, projects implemented by producers outside of the watershed council’s efforts, and streambank restoration projects undertaken by Wisconsin DNR and the Trout Unlimited Driftless Area Restoration Effort.”

Grasslands 2.0

Heisler made it clear that monitoring the positive impacts of the project on water quality in the creek would be a long-term project. In the interim, another facet of the project was collaboration with UW-Madison and the Grasslands 2.0 project, and the Wallace Center Pasture Project, on development of the ‘Grazescape’ tool, which allows the positive impacts of implementation of managed rotational grazing to be modeled.

“The positive impacts of the project as modeled through ‘Grazescape’ give us an estimate, and something to compare future water quality measurements to,” Heisler explained.

Grassland 2.0 is a collaborative group of producers, researchers, and public and private sector folks working to develop pathways for producers to achieve increased profitability, production stability, and nutrient and water efficiency, while improving water quality, soil health, biodiversity, and climate resiliency through grassland-based agriculture.

The program spans multiple states, and taps a variety of different subject matter experts. One of the tactics used in Grassland 2.0’s work is to convene ‘learning hubs,’ where they can take a deep dive into a region, work with local producers, share information and learn. One of those learning hubs was convened in the Driftless Region.

Local grazers Jim Munsch and Dennis Rooney, along with many Driftless Region producers, worked with Grassland 2.0 to develop the ‘Grazescape’ tool, which is based on a SnapPlus meta-model.