A group of about 30 citizens enjoyed a tour of parts of Tippesaukee Farm near Port Andrew on Sunday, April 27. Dr. Eric Carson of the Wisconsin Geological and Natural History Survey discussed how natural features on the landscape provide clues about how the rivers that flowed shaped the landscape.

Geomorphology is the scientific study of landforms and the processes that shape them, both on Earth and on other planets. It focuses on understanding how natural forces like erosion, deposition, and tectonic activity modify the Earth's surface.

Ben Moffat, descendant of John Coumbe, the first European settler in Richland County, welcomed the group to the farm.

“Tippesaukee Farm has always been a gathering place, first for the Ho-Chunk and Meskwaki people, and now as the Crosscurrents Heritage Center,” Moffat said. “Right now, the Center is entirely volunteer powered and funded through donations. Throughout 2025, my brother Bruce and I will match any donations of $100 or less.”

Most of the citizens present had heard Dr. Carson’s lecture-style presentation at the farm in the fall of 2024.

“We’re not going to sit around in the barn today – we’re going to go out and walk and look at the features on the landscape,” Carson said. “However, I’ll give a short overview of what I discussed in my presentation last fall.”

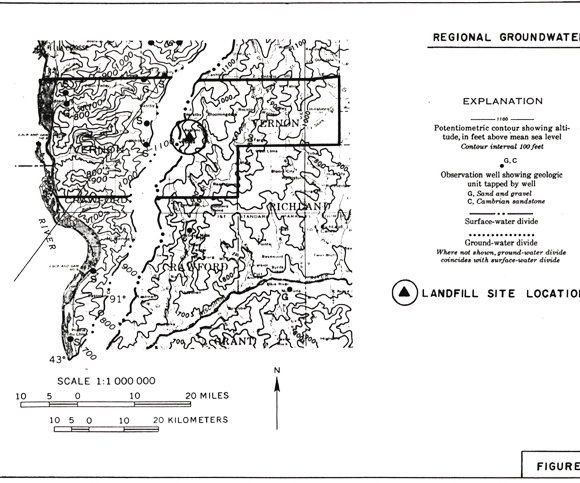

Carson said that evidence suggests that between 1-1.5 million years ago, before human habitation on the planet, another river flowing from the west had carved out the valley where the Lower Wisconsin River currently flows. He said that geologists refer to this river as the ‘Wyalusing River.’ That river, he said, flowed from west to east, and ultimately flowed through Green Bay into the St. Lawrence Seaway, and then into the Atlantic Ocean.

“I just want to make clear that the Wisconsin River never flowed west,” Carson was quick to clarify. “The Wisconsin River, after the glaciers that held back historic Lake Wisconsin melted, grabbed the bed of the historic Wyalusing River like a hermit crab, and then joined with the newly created Upper Mississippi River to flow west and the south after the confluence with the Upper Mississippi River at Wyalusing.”

Carson said that terraces, like the one where Tippesaukee Farm is located, provide some of the evidence supporting the existence of the Wyalusing River. In flowing west for millennia, that river had eroded its course down and into to the bedrock.

“The terraces closer to the river are filled with 150-200 feet of sand and gravel, outwash from the glacial melt,” Carson explained. “Terraces like the one on this farm have only 10-15 feet of sediments overlaying the bedrock.”

The bedrock on the terrace at Tippesaukee Farm continues to near Frank’s Hill, and Light Detection and Ranging, a remote sensing technology (Lidar), shows us that this bedrock is eroded to tip down to the east. This, Carson said, demonstrates that an east-flowing river, over the course of millennia eroded the river course. He said that the level of the terrace used to be the level of the entire valley floor.

The farmhouse

The group exited the barn, and walked to the yard in front of the Coumbe family farmhouse, overlooking the Wisconsin River.

“Historically, the elevation level of the Wyalusing River would have been the same as the front yard we’re standing in now,” Carson said. “Another piece of evidence for an east-flowing river is that the tributaries of the Lower Wisconsin River flow to the east, and are referred to as ‘barbed tributaties.’ Water will always flow from the higher point to the lower point, and this is another piece of evidence demonstrating that the elevation of the bedrock of the current Wisconsin River bed decreases in elevation from west to east.”

One participant pointed out that the Kickapoo River doesn’t fit this pattern, and asked why.

“The Kickapoo River is a weird river, unlike anything else in the region,” Carson responded. “As a tributary it is much larger, and flows a longer distance from its headwaters in Monroe County than the other Lower Wisconsin River tributaries. Given this, the Kickapoo River had the power to carve down into the sandstone layers to the level of the valley floor.”

Getting back to the Wyalusing River, Carson said that at a point in time, a glacier descended from the north and east, and blocked the eastward flow of the river. Carson said that would have created a glacial lake, backed up all the way to Wyalusing.

“Twenty-to-thirty thousand years ago, the glacier melted, releasing melt and debris, and the cataclysm reversed the flow of the river, carved further down into the river course, and over the course of 10-15 thousand years, pumped out sand and gravel which filled the river course in.”

According to Carson, there was a glacier at an even earlier time that came from the north and the west, and blocked the river’s flow near Bridgeport, creating another glacial lake.

“That glacier was the one that covered areas in Iowa and Minnesota that are often referred to as the ‘Driftless,’ but aren’t, and the glacier that defined the boundaries of the true Driftless Region (unglaciated) in Wisconsin and Jo Daviess County in Illinois”

Carson said that the terrace where Tippesaukee Farm is located is a remnant of the bed of the Wyalusing River from 1.5 to 2 million years ago, before humans were present.

Walk in the woods

Leaving the yard of the farmhouse, the group walked into a woodlot on the eastern edge of the farm. At the edge of the woods, the view opened up into farm fields that extended to the edge of forested hillsides.

“The top layer of bedrock on this terrace, which extends east to Frank’s Hill is the Tunnel City Sandstone, characterized by a distinctive green color,” Carson said. “From here, if you look to the north, you can see where the edge of the terrace is as the type of bedrock changes to harder rock formations – that’s where the agriculture ends and the forested hillsides begin. So, when the Wyalusing River was flowing east millions of years ago, where you’re standing would have been the valley bottom and in the river.”

As the group continued to walk through the woodlot, Carson explained that, for Wisconsin, some of the geological artifacts on the terrace are very old. He said the edge of the glacier that had come from the north and east can be found near Verona and Cross Plains, and the geological artifacts there are about 15,000 years old. By contrast, the geological artifacts on the terrace where Tippesaukee Farm is located are 1.5 million years old, or older.

“In this area, when you use a probe to go down 1.2 feet, you find a very strange soil, with lots of little pebbles, which is not present elsewhere in the river valley,” Carson said. “Historically, when the Soil Conservation Service mapped the soils in the area, the soil scientist doing the mapping reached out to elders in the Ho-Chunk Nation to select a name for the soil type.”

Typically, the names of soil series are limited to 12 characters, but an exception was made for the Nuxmaruhanixete series, which contains 18 characters.

Fire pit stop

The last stop on the tour was at one of two partially cleared areas in the east woodlot where oak regeneration projects are in progress. The second location is also being developed as a permanent location for fireside talks.

Carson pointed out that, though it is partially concealed by vegetation, the landscape on the terrace has a disorganized look to it, with lots of ups and downs.

“During the glacial times, in this northern latitude, it was very cold, and the ground was frozen with permafrost 1,000s of feet deep,” Carson said. “This inhibited the growth of vegetation, leaving the area bare. Glaciers produce a lot of clay, silt and sand, and when they melt, and things dry out, then it gets picked up by the wind and moved.”

Carson said that clay is the finest particle, and when picked up by the wind can be lofted high in the air and travel globally. Silt, he said, is the next finest, and can be carried quite a way by the wind, but then tends to fall back to the earth. This silt, referred to as ‘loess,’ is the source of the fertile farm soils in the region. Sand, he said is the biggest and heaviest of the particles, and can’t be carried very far by the wind before falling back to the ground.

After the climate warmed and the glaciers melted, then because there were no living roots in the wind-deposited soils, they would be moved around in a very chaotic fashion. Eventually, it would become vegetated, and then the shape of the land would become locked in place.”

Carson said that silt is the smallest material made by the grinding of glaciers. He said that by contrast, clay is not formed by glacial grind, but rather by a chemical process of the weathering of rock.

Upcoming events

Ben Moffat shared some upcoming events planned for 2025 by the Crosscurrents Heritage Center:

Sunday, May 18: Ho-Chunk music and dance by the ‘Wisconsin Dells Singers & Dance Troup.’ Pre-registration is required at crosscurrentsheritage.org, and donations are gratefully accepted

In the late summer or early fall, a Nature Walk on the Farm, and a Farmhouse Tour are also planned.