In 2019, the Dane County Board of Supervisors approved bonding for $750,000 to support Land Conservation in implementing an innovative ‘Continuous Cover Program (CCP).’ The program was intended to improve water quality, reduce soil erosion, build soil health, enhance wildlife habitat, diversify production practices, make sure farms stay sustainable by having different landscapes, and sequestering carbon.

“Each year after that, we've had either a million to $2 million in bond money added to that pot for implementation of this program,” Dane County Land Conservation Director Amy Piaget told land conservation professionals from Monroe and Vernon county. “The funding came with a lot of practice funding, but no funding for additional staff, so we had to kind of absorb this program into our standard workload. As far as cost share rates, we pay a rental payment, very similar to the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) of $2,250-per-acre for a 15-year contract. That amounts to $150 an acre per year. The amount includes $125 in rental, and $25 per acre for ongoing maintenance.”

Piaget was presenting information about her county’s innovative conservation programs to professionals from the Monroe and Vernon county Land Conservation Departments, as well as members of the Monroe County Climate Change Task Force (CCTF). The group traveled to Dane County as part of CCTF’s annual summer field trip.

Program funding

“This is a county-funded program that is very similar to the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP),” Piaget explained. “There are differences, but if you're familiar with CRP, it's similar. But, it's at the county level, and basically we convert annual row crop fields to either perennial, cool season grass mixes; or native mixes. So prairies, we do grazing, managed grazing, and we've just started in the past few years implementing trees as well. So incorporating trees into our CCP mix - not reforestation, when we say trees, but more of a silviculture approach.”

Piaget said that in the past two years, they had started offering a permanent easement, so if a landowner wants to participate in the continuous cover program, but they want to permanently set aside their land, her department offers a permanent easement, and that's for $4,500 an acre. She said the payment for a permanent easement is basically double that paid for the 15-year contract, is recorded on the deed for the property, and follows the property even in the event it is sold.

“We will also cover 70% of grazing infrastructure – so, fencing and watering are the two main things, and then we also cover the seed establishment,” Piaget told the group. “We offer cost share for non-native plantings of $150 an acre, and $250 an acre for native seeds. And if you're doing trees, we do $15 a tree.”

Piaget explained that when they talk with landowners, they offer their CCP program, but also offer CRP because they work closely with USDA’s Natural Resource Conservation Service (NRCS). She said that CRP offers an annual payment, whereas the CCP program gives a one-time lump sum payment.

“Most of our longer-term contracts were rolled over from 15-year easements, so they're just getting another 20-50 years. I don't think any of them have gone in as permanent,” Piaget said. “A lot of times, it's folks who have done native plantings that are looking at doing permanent easements because they've invested in the natives, and they're managing it as a prairie, so they're more likely to do a permanent easement.”

One Monroe County Climate Task Force tour participant asked if the lands enrolled in the Continuous Cover Program would be eligible for emergency hay production, for instance if a significant drought develops, like lands enrolled in the CRP program?

“We haven't dealt with it yet,” Piaget responded. “We might follow CRP because we generally follow CRP planning for the seamlessness of it. So we might consider that if there was that kind of emergency.”

Application process

Piaget said that when the initial announcement of the program was made in 2019, they experienced a ‘rush’ of landowners interested in accessing the funding.

“It was a big announcement, and we had a kind of a rush of people,” Piaget explained. “We made it pretty complicated the first year. We also developed our contract language, which incorporates what we call ecosystem services, and specifies that we get the credit for the carbon and the phosphorus reductions.”

Piaget said that after that initial rush, interest in the program had leveled off at a more manageable level.

“We've kind of stepped it back, so we don't really do a ranking anymore, but we're not getting so much interest that we don't have enough money to cover the interest,” Piaget said. “If we had a big lot of applications and not enough funding to cover them, we might have to go back to some type of prioritization. We still stick to our prioritization criteria of highly erodible lands, proximity to lakes and streams, and encouraging pollinator habitat. But, we don’t make it overly complicated.”

Piaget said that when land is proposed for conversion, they require a cropping history easily obtainable from the Farm Services Agency (FSA). And, when investing in managed grazing systems, the operator is required to have a nutrient management plan. She said that in all cases where funding is requested, the operator is required to be in compliance with Dane County’s ordinance, which is basically the same as state standards.”

Participation

Piaget said that for 2019 applications they had 21 applicants funded. In 2020, they had 28, and in 2021 they had 41, which she said began to exceed the capacity of their staffing levels. She said that since then, applications seem to have hit a plateau, with typically about 20 applications per year.

“Looking at our maps of the types of cover we’ve funded, we have impacted about a total of 2,700 acres,” Piaget said. “Of that, about 800 acres are in native plantings, 900 acres are in managed grazing, and 1,000 acres are in cool season grasses.”

One audience member asked how often Piaget’s department inspects lands enrolled in permanent easements?

“We inspect permanent easements annually, and this had led to a conversation about how many we can handle at current staffing levels,” Piaget responded. “We're looking for encroachment - we don't want any buildings on there, or to see landowners cropping it.”

Measurement

Watershed and Ecosystem Services Division staff member, Michelle Probst, discussed the ways that the impacts of the CCP-funded practices are measured. She said the goal is to document the impacts of the practices for sequestering carbon, and for soil erosion and phosphorous in surface water reduction.

“Where we live in Madison, they love the lakes and they love the environment,” Probst explained. “So, it's really the community that has supported us to become a high capacity unit. I’m within our watershed and ecosystem services division, and we're kind of like the data and quantification nerds who calculate the impact of the investment that we're making in all of these different programs.”

Probst said that the big ecosystem service that they're really talking a lot about is carbon benefits in support of their goal of carbon neutrality.

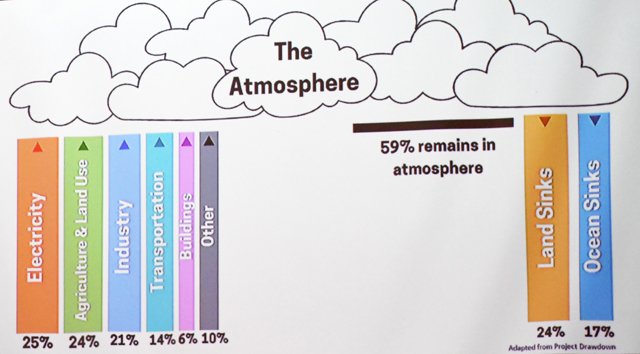

“When we're talking about greenhouse gas concentration within the atmosphere, we have all of these inputs, right?” Probst said. “Project Drawdown is a really great resource, and has lots of different solutions. They say that a significant portion of carbon emissions generated globally are still in the atmosphere. So while we need to cut emissions, we also need to support carbon sinks in our lands and oceans that actually have the ability to draw down greenhouse gasses out of the atmosphere and store them.”

Probst said that in the Midwest, the most important opportunity lies in carbon sinks in the land.

“Soil is the largest terrestrial carbon sink on the planet, so if we manage our soil better, it can actually hold or take carbon out of the atmosphere and store it long term,” Probst explained. “How we can store more carbon in the soil is really by increasing our inputs and decreasing our losses. Carbon gets into the soil through plants and through plant roots. The way we get the maximum amount of inputs of carbon into the soil is through diverse living root systems, especially perennial systems. On the other hand, when we till the soil or disturb the soil, that actually breaks apart the soil and exposes carbon, and you're losing carbon back to the atmosphere. So, if we can do this simple formula of increasing inputs and decreasing our losses, we can gain carbon in the soil.”

Probst pointed out that in addition to working with county landowners, their department also works on restoration projects on property they own.

“Our Park system is about 17,000-18,000 acres, a large land base that we that we own and operate,” Probst pointed out. “So that's kind of what it comes to us as. A lot of times, especially on ag land, we are then restoring it back to tall grass prairie. We feel it, it's managing the land for future generations.”

Probst said that because of capacity limitations due to staffing, it’s often not possible for them to restore the land as fast as they receive it. However, she explained, it remains an opportunity for them.

Quantification

Probst said that her team is involved in quantifying the carbon sequestration happening on lands with CCP-funded projects or county lands where restoration has taken place.

We're quantifying carbon sequestration through direct, direct measurement of soil,” Probst said. “What we did is we took the CCP program, which is a relatively new program, and we took about 1,000 acres within our Dane County Parks that's considered newly planted, and we took soil cores to be analyzed to understand how much carbon is in the soil right now. So, we established a baseline for that.”

Probst said the soil core is divided into topsoil and subsoil segments for purposes of analyzing stored carbon. She said that over the years of sampling periods, if they see growth in carbon stored in the subsoil, that will indicate long-term soil carbon storage.

“We'll come back in five years, 10 years, 15 years, because this process takes a long time, and we’re in this project for the long haul,” Probst said. “What we can do in the interim to show and quantify the benefits of these landscape modifications is through modeling.”

COMET Planner

Probst explained that USDA and Colorado State University have developed a COMET Planner tool, a greenhouse gas accounting model, and it models how carbon can accumulate in the soil.

“So our approach is to do this where we're looking, getting the actual sample, but then also modeling,” Probst explained.

Probst pointed to one parcel that had come to Dane County as agricultural land farmed for cash grain. They had since planted that parcel into tallgrass prairie. She says the COMET planner can quantify the carbon impacts of the land under as-received management, and then quantify the carbon impacts of the newly implemented land use, and then calculate the carbon sequestration gains of changes made.

“So we look at our agriculture scenario, and we may be sequestering some carbon, but we're losing nitrous oxide and we're losing some carbon,” Probst shared. “And then with our prairie system, you can see we are we're storing a lot more carbon. We're losing some nitrous oxide, but really we're storing more carbon to kind of cancel out that emission, essentially.”

Probst said that in her 100-acre field example, they're gaining 76 metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent per year. She said that for all the public parcels of land, her department had launched a dashboard showing modeling results for the public to access. She said her department can’t show the impacts on private lands funded through the CCP program to protect landowner privacy.

“But internally, we know that for the acres enrolled in the CCP program, we’re gaining about 2,500 metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent,” Probst explained. “And, right now on our public lands, we’re gaining about 3,500 metric tons.”

Probst said that they're essentially doing a ‘carbon in-setting program. She said that right now, their county operations are emitting right around 17,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide, and they are sequestering 3,500 on lands they own. She said that the goal is for these two to be in line.

“So what that means is our Climate Action team is really leading the charge on how we’re going to reduce and cut our county’s emissions, and our team is working to see how we can get more acres enrolled in Continuous Cover Program and how can we get more restoration done on our parks properties,” Probst concluded.