Wisconsin DNR Wildlife Biologist Dan Goltz, based out of the Viroqua office, gave a talk about ‘Bald Eagle Status and Monitoring in Wisconsin.’ The talk was part of Valley Stewardship Network’s ‘Conservation on Tap’ series, and took place at the Hotel Fortney on Tuesday, November 4.

“Eagles have a wide geographical presence, both in Wisconsin and throughout the U.S., wherever there's good habitat,” Goltz explained. “We know that their reproduction is sensitive to contaminants, and they live and forage in aquatic habitats, where different types of pollution is often concentrated, and so they've been proven useful as an indicator species of ecosystem health.”

Goltz said that WDNR’s survey started in 1973, when eagle populations were in collapse from use of the pesticide DDT, and also encompassed the impacts of PCBs present in the Fox River Valley, Green Bay and Lake Michigan from dumping by paper mills. However, since the survey re-started in 2022, after a four-year pause, the focus has shifted to emerging contaminants like PFAS.

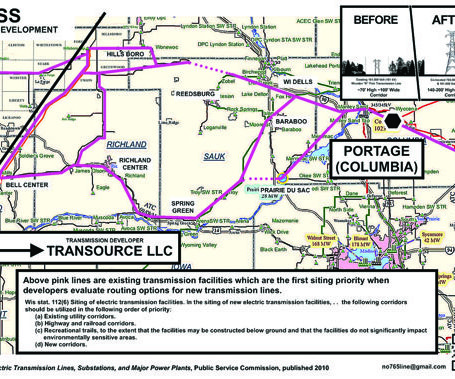

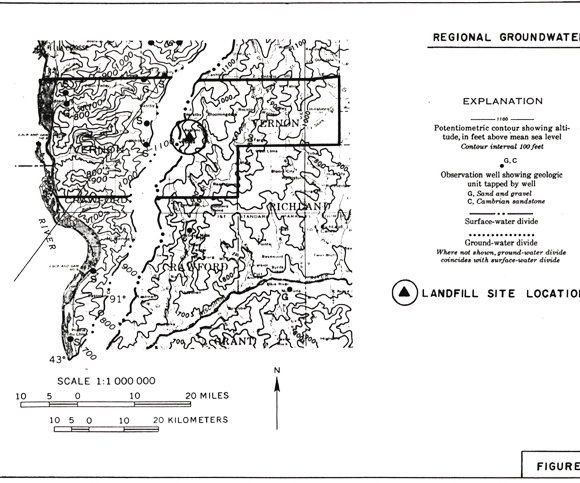

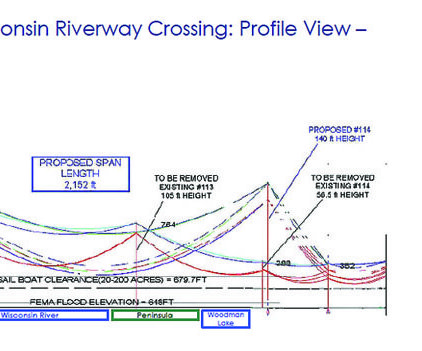

“The group of chemicals known as PFAS is contributing a huge load to eagles in the middle stretches of the Wisconsin River and the Lower Wisconsin River, as well as other parts of the state,” Goltz explained. “Part of the reason for these really high levels of PFAS in particular in the middle and lower Wisconsin River isn't necessarily associated with one point source, like a factory along the river, but rather just that the Wisconsin River drains such a big watershed, that these chemicals are just ending up there.”

He said that while eagle reproduction rebounded after use of DDT was banned, and the impacts of PCBs declined after the Fox River was dredged, “emerging contaminants, especially per- and polyfluorinated compounds, are increasing, and we need to figure out more specifically how those are impacting eagles and other wildlife species.”

It takes a team

Goltz said he has now joined in the work with UW-Madison Sea Grant researchers Gavin Dehnert and Emily Cornelius Ruhs. Dehnert is an Emerging Contaminants Scientist/Bander, and Cornelius Ruhs is an Ecoimmunologist. The two are project co-leads for Sea Grant’s ‘Great Lakes Eagle Health Project,’ working under project lead Sean Strom, a Fish & Wildlife Toxicologist with WDNR.

Their multidisciplinary project team consists of federal, state, and academic researchers and technicians from their many project sponsors, including Wisconsin Sea Grant (part of the UW-Madison Aquatic Sciences Center), Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, the Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission (GLIFWC), the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, and the Field Museum of Natural History (FMNH).

The project has tracked reproduction success and contaminant levels in eagles across Wisconsin since 1990, with an emphasis on eagles nesting along the Great Lakes shorelines. The team is studying how contamination influences eagle health, which can also tell us how pollution impacts ecosystems and people.

The two main goals of this study are to:

• assess the concentration and source of PFAS contamination in the dietary niche of bald eagles at known PFAS-contaminated sites; and

• compare the physiological and immunological health of eagles in Wisconsin across a contamination gradient.

“In 2023, we sampled nests along Lake Superior and the Apostle Islands, and in 2024 we were back at Lake Michigan, Lake Superior and the Apostle Islands. This past summer, we did the Wisconsin River again,” Goltz said. “Next summer, we're going to do the Mississippi River, and then the St. Croix and so on. They've got some good funding from NOAA.”

Goltz said that PFOS are really high in the middle and lower Wisconsin River. What does this do to eagles? He said they know for sure that it has a negative impact on endocrines (hormones), and that can impact eagles’ thyroid function, decrease reproductive success, hatching success, and affect nesting behavior.

“In summary, PFAS were detected in every bald eagle population that we sampled. Most of the populations are below current thresholds for PFOS, but individuals might be above it in certain areas,” Goltz explained. “Thresholds for other PFAS are not well established or established at all. So we are using blood from an eaglet to tell us about how healthy the ecosystem is, and how the health of that ecosystem changes over time. And the big take home point Sean Strom, our main researcher, really tries to make clear to everybody is that eagles are eating the same fish and the same deer and the same everything that I'm eating, and probably a lot of you people are eating too.”

History of surveys

According to Goltz, WDNR conducted Bald Eagle Surveys continuously between 1973 and 2018. The surveys involved what is called an ‘occupancy flight’ in an airplane in late March to survey all known nests to see if adults were present, and if nesting activity was occurring. Nests were classified as either active or inactive. Then in mid-May, another flight called a ‘productivity flight’ would occur over all known nests to determine if there were young in the nests, and to count the number of young.

The number of occupied eagle nests across the state increased dramatically between 1973 and 2018, increasing from around 100 in 1973 to over 1,500 in 2018.

Goltz said that originally, WDNR’s eaglet sampling effort, referred to as the ‘Wisconsin Bald Eagle Bio-Sentinel Program,’ got started with sampling eagle populations in different regions of the state for ‘DDE,’ a compound that is the byproduct of the pesticide DDT.

Widespread use of DDT from 1947 to 1970 had caused eagle populations to decline drastically. DDE causes the shells of eggs of eagles to become weak and fragile, and the weight of the adult eagle incubating the egg would cause it to fracture. Use of DDT was banned in 1972.

Even as late as the period 1990 to 2002, eaglet blood sampling was still revealing elevated levels of DDE. Levels above the 11 micrograms threshold which can be lethal to eagles.

“In some of the same territories that we visited again in 2011 or 2012, you can see that much of the DDE was getting leached out of the system or no longer available to eagles,” Goltz stated. “So, we saw a significant change over time, but there was still elevated levels in Green Bay and Lake Michigan, likely a legacy of use of DDT in the orchards in Door County.”

Other issues

The program also looked at PCBs, a contaminant particularly prevalent in the Fox River Valley, Green Bay and Lake Michigan.

“I think, 350 tons of PCBs were dumped into the Fox River by paper mills that resulted in degraded fish and wildlife habitat, impaired avian reproduction, and still results in fish consumption advisories in some areas,” Goltz explained. “Going back to that 12-year time period from 1990 to 2002, sampling showed elevated levels of PCBs along the Lower Fox River. And then, fast forward to 2011 and 2012, the levels of PCBs had declined drastically on the Fox River above the dam at De Pere, and that's because of the dredging and clean-up of the sediment in the Fox River. That got the PCBs out of the system for those birds, but we still see elevated levels out in Green Bay.”

Goltz said the program also looks at lead in eagle blood, which was the second leading cause of eagle mortality in data from the study in the 2000-2007 time frame.

“Our wildlife health lab did necropsies on over 500 eagles in the early 2000s, and attributed the cause of mortality to different categories. Trauma was the most common cause of death, and then lead toxicity was tied for second with unknown causes.”

Goltz said that in the ‘trauma’ category, vehicle collisions were the most common cause of eagle death in birds feeding on road kill along the sides of roads. When it came to lead toxicity, he pointed out that eagle deaths from lead poisoning peak in November and December in Wisconsin, which he links to use of ammunition containing lead during deer hunting.

“There's a direct link between deer that are shot with lead core bullets being left on the landscape and eagle mortality,” Goltz explained. “What happens with lead core bullets is that they fragment into hundreds of tiny little flecks, which in analysis almost appears like lead dust.”

“As an alternative, there are a lot of factory pre-loaded ammunition that you can buy where the bullets are solid copper, and they don't have any lead in them,” Goltz said. “Just a tiny little bit of lead is enough to kill an eagle. So if you think of it like a number four bird shot that you might use for waterfowl, or if you were able to cut that up into five different pieces and feed one piece of that to an adult eagle, that would be enough to kill that bird.”

Why monitor eagles?

Goltz listed the reasons why eagle-monitoring programs are important:

• established monitoring programs exist

• eagles have a wide geographic presence

• eagles are sensitive, as apex predators, to contaminants

• eagles live and forage in aquatic habitats where pollution is often concentrated

• eagles have a proven utility as an indicator species

• monitoring provides insight to contaminant exposure in Wisconsin wildlife, and is useful for multiple agencies and programs.

He said the objectives of the eagle-monitoring program are to:

• determine levels of contaminants in blood plasma from the Green Bay/Lake Michigan/Lower Fox River eagle population between 1990 and 2013, and since then, in other regions of the state

• examine the relationship between contaminant levels and reproductive rates

• explore trends of newly emerging contaminants

• assess the utility of bald eagles as indicators of environmental health and change.

Goltz detailed the methodology of the monitoring work they do. First, reproductive rates of nests are assessed by aerial survey out of a plane and citizen science. Then, when the eaglets are 5-8 weeks old, their blood plasma is analyzed for organic contaminants.