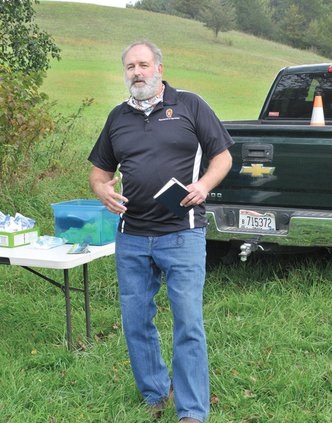

DRIFTLESS - Professor Randy Jackson travelled out to the Kickapoo Valley on Saturday, Sept. 26 for a presentation on ‘Can managed grazing improve soil health & water quality in the Driftless Area?’ The talk was part of the ‘Driftless Dialogue’ series sponsored by the Kickapoo Valley Reserve.

About a dozen citizens were on hand to listen to the professor of Grassland Ecology in the Department of Agronomy at UW-Madison discuss the Grassland 2.0 project. The project has been funded through a five-year, $10 million grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Institute for Food and Agriculture. It is based at UW–Madison.

According to their newwebsite, Grassland 2.0 is a collaborative group of more than 30 scientists, educators, farmers, agencies, policymakers, processors, retailers, and consumers working to develop pathways for increased farmer profitability, yield stability and nutrient and water efficiency, while improving water quality, soil health, biodiversity, and climate resilience through grassland-based agriculture.

“The vision of our project is really to help to transform modern agricultural production to increase farm profitability, while replicating all of the ecosystem benefits that the area’s original perennial grasslands provided,” Jackson explained. “Through the process our goal is to implement a ‘JEDI’ system – justice, equity, diversity and inclusion.”

Problems with ag

Jackson seemed to feel it was appropriate to be talking about his project in the Driftless Area of Wisconsin.

“This area, from Aldo Leopold and the Coon Creek Watershed Project and forward, is renowned for its response in times of environmental crisis,” Jackson said. “When soil erosion and flooding had wreaked havoc on the environment, citizens in this area did a beautiful job of joining together to put things back in place, and protect lives, livelihoods, infrastructure and the ecosystem.”

Jackson contrasted the heroic efforts in the area in the 1930s through the 1970s, with some of the shifts in agricultural land use and practices that have evolved since then.

“Modern agricultural production methods are basically rife with problems,” Jackson explained. “It all involves a gouging out of the earth, and it seems that no amount of bandaids can stop the system from being leaky – that is failing to prevent excess nutrients from reaching ground and surface water, keeping soil in place, and infiltrating enough water in the soil to prevent runoff and flooding.”

Jackson said that the pollution in the state’s waters, at least in the last 100 years, has primarily come from agriculture. He said that at some point, we have to ask ourselves why our production is primarily based on growing corn and soybeans.

“Most of the corn (40 percent) is used for feeding livestock, 35-40 percent for ethanol, and 15-20 percent for high fructose corn syrup,” Jackson explained. “Soybeans are primarily used as a food additive, and the oil is used for livestock feed.”

Jackson says that it is crucial at this time in history that we ask ourselves – “Is this how we want to produce livestock?” Jackson also explained that the corn and bean monocultures were having a devastating effect on biodiversity, and impacting the declines of birds and pollinators.

“Livestock can feed themselves, and they can spread their manure and their urine themselves as well,” Jackson said. “But to really make a positive impact on farm profitability and yields, as well as on protecting and enhancing ecosystem services, we need to see a transition away from continuous grazing to well-managed grazing.”

Profit and satisfaction

Jackson said he has spoken to more than one farmer who has made this transition, and heard about not only enhanced profitability, but also about increased job satisfaction.

“Making a transition like this drives the farmer back to the land, and provides the challenge and satisfaction of being adaptive,” Jackson said. “What farmers tell me is that this is a considerable and unanticipated side benefit of making the shift.”

One example Jackson described was of a Dane County dairy farmer, Bert Paris.

“Bert Paris loves dairy farming. After more than 30 years, he’s beginning to transition the farm he operates near Belleville, Wisconsin, to his daughter, Meagan Farrell, who is ex-cited about moving her family home to run it.

“Despite years of terrible headlines about the dairy industry, farmers like Paris and Farrell are bullish on dairy because, despite chronically low and erratic milk prices, they’ve con-trolled their production costs with managed grazing.”

“Grazing, financially speaking, was the best thing I’ve ever done for my business,” Paris says.

Grassland-based farming practices represent a bright spot in an industry that is feeling the combined effects of low commodity prices, extreme weather events, rising production costs, and limited processing and marketing options. Consumer data suggest that while red meat and milk consumption are declining overall, both grass-fed dairy and meat sales are surging.

A multi-decade analysis by the UW–Madison Center for Dairy Profitability found that although grazing-based dairies often produce less milk per cow, the money they save by grazing ultimately increases their profitability.

Benefits of doing it right

Jackson contrasted continuous grazing versus well-managed grazing, and helped event participants understand the benefits that come from “doing it right.”

“Continuous grazing, doesn’t give the pasture time to recover, encourages undesirable plant species, and reduces the ability of the grass to hang on to nutrients and water,” Jackson explained. “Well-managed grazing, in contrast, maintains a dense stand of clover and grasses, which suppresses weeds, and develops a deep system of roots which infiltrates water, and prevents nutrients from running off or percolating down into groundwater.”

Jackson quotes one of his managed grazing mentors, Spring Green grassfed beef farmer Dick Cates about the benefits of well-managed grazing.

“Dick Cates will tell you that making the transition to well-managed grazing is like putting money in the bank,” Jackson said. “According to Dick, in addition to increased profitability, the benefits include increased productivity, enhanced biodiversity, healthy trout streams, and increased bird habitat.”

Impact on climate

In addition, Jackson said that well-managed grazing has great potential to help slow and reverse the impacts of climate change, which he says is disproportionately impacting farmers.

“Well-managed grasslands take carbon out of the atmosphere and store it at depth in the soil, Jackson explained. “Our studies at the Arlington Research Farm show that the prairies this area had in the past were able to store tremendous amounts of carbon.”

Jackson said that his work at the university is at what he describes as the ‘frontier of soil science.’ He and his colleagues have dedicated their work to answering the question “why isn’t the soil storing more carbon?’ He says that the answers aren’t as simple as they might seem. Part of the problem is that, from a climate perspective, the pace of change and deviations from the old normal mean that scientists are struggling to keep their models up to date with changing conditions.

“With climate change, we’ve seen that the nights, winters and springs are becoming generally warmer,” Jackson said. “This means that even if there is no plant growth, the soil microbes are still waking up sooner, and doing their thing.”

The research at Arlington has now been ongoing for about 30 years. The team has previously been basing their research and conclusions on cores drawn from fields maintained in various cropping systems after 20 years. They have only recently drawn new 30-year core samples.

“What we found after 20 years was that the only system accruing carbon was managed grazing with cool season grasses,” Jackson said. “Most of this carbon is being stored at less than a meter into the soil, but when we take cores that are deeper than that, what we’re finding is 500-year-old carbon that was stored by the prairie systems.”

Other factors

Jackson emphasized that in addition to research to understand what the best production models are for well-managed grazing, his team is also taking a much broader approach. That approach will take into account the social, political, economic, and market factors that can be an impediment to a producer making the decision to transition.

“We have already seen a massive shift in agriculture in Wisconsin with the catastrophic loss of small to mid-size dairy farms,” Jackson said. “In 2003, the state had 16,000 dairy farms, in 2020 it has just 7,000 dairy farms, and is on pace to have only five dairy farms by 2030.”

Our project aims to address the social issues of “what it means to be a farmer.” A lot of these issues are things that are very personal to the individuals involved, such as not wanting to be critical of the previous generation or feeling loyalty toward peers.

Learning hubs

For this reason, Jackson said, the Grasslands 2.0 project involves plans to convene various ‘learning hubs’ around the Upper Midwest with the goal of gathering together groups of people that “usually don’t talk.”

Jackson said that his group is in the final stages of evaluating proposals from different groups of stakeholders about where the learning hubs will be based. He says the final decisions will be based on the enthusiasm of the local stakeholders for the project, and final choices will be announced in mid-November.

Jackson’s colleague Dr. Eric Booth has created a simplified version of the SNAPlus program, that farmers can use to quickly and easily model what different land use choices might look like on their land. These will be accompanied by an economic analysis of what impact making those transitions might have on the farm’s profitability.

The model for the learning hubs will be to convene groups of stakeholders, including local farmers, county, state and federal agency staff, and even interested citizens, to participate in a series of visioning sessions.

“Our hope is that we will be able to catalyze a transformation of consciousness and practices with our models,” Jackson said. “What we want to demonstrate is the connections between transforming of the landscape, and the transformation of farm economics and ecosystem services.”

For more information about the project, go to their new website at: www.grasslandag.org