LACROSSE - It has been 30 years since the very first local organic farming conference drew about 90 participants to a wedding hall on the south side of LaCrosse–a lot has changed since then.

The MOSES Organic Farming Conference held at the LaCrosse Center in late February drew over 3,000 people. There were 72 workshops, 15 roundtable discussions, two keynote presentations and a large tradeshow.

While the conference was a far cry from that original 1989 conference, it was somehow inextricably linked to that first event. Nowhere was that linkage clearer than at Friday’s keynote presentation, which featured six of the organic movement’s old guard.

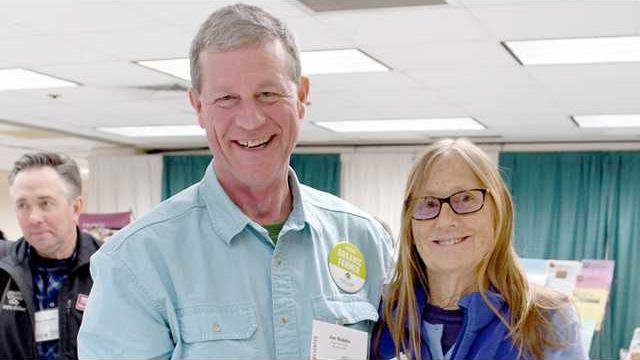

The OG panel included George Siemon, Jim Riddle, Faye Jones, Atina Diffley, Francis Thicke and Audrey Arner.

George Siemon was an early organizer of Organic Valley, when it was still known as CROPP (Coulee Region Organic Produce Pool). He has served as the only CEO of Organic Valley. He also served on the National Organic Standards Board.

Jim Riddle has played an instrumental part in the organic movement. Among the many positions he has held, Riddle has served on the National Organic Standards Board. Jim and his wife Joyce Ford own Blue Fruit Farm near Winona and were selected the 2019 Moses Organic Farmers of the Year.

Faye Jones was part of the group that established the organic farmer conference. She served as the first director of MOSES for over 17 years. She is a consultant, volunteer and farmer raising grass-fed beef with her husband on their farm in Wisconsin.

Atina Diffley is a longtime organic vegetable grower, who ran Gardens of Eagan in Minnesota with her husband Martin. Atina is also an author who wrote ‘Turn Here Sweet Corn: Organic Farming Works.’ She also served on the MOSES board.

Francis Thicke has a doctorate degree in soil science and has been an organic farmer for over 30 years. Francis served on the National Organic Standards Board and was on the first MOSES board.

Audrey Arner has a perennial polyculture farm in Minnesota, with grass-fed beef, fruits, nuts, ornamentals, medicinals, art and farm stays. She served on the MOSES board for six years, and as president for two years.

“These elders in the organic movement explore the movement’s roots, the origin of the MOSES Conference 30 years ago and their vision for the movement’s future,” the conference program promised. And, the panel delivered on that promise.

The comments began with MOSES 2019 Farmer of the Year Jim Riddle.

“My first exposure to organic growing methods was not called organic,” Riddle explained. “It was called natural farming–food grown naturally. It was Rodale that coined the ‘organic’ definition.”

Riddle explained that as organic growing was taking hold in the northeast, the northwest, the Midwest and California, standards developed regionally that were similar, but also had quite a few differences. For instance land in the Midwest needed to be free of ag chemicals for three years to qualify as organic, while the standards in California required just one year of being chemical-free.

“So, we go to D.C. in the late 80s and say ‘please regulate us’,” Riddle said.

Then, in 1990, the USDA passed the organic standards, but it was 12 more years before they were implemented in 2002 under the National Organic Program.

Riddle urged everyone “to stay true to our roots.”

“It’s still our word, ‘organic’ and our regulations, if we say it’s the USDA’s we gave it away,” Riddle said. “So, stay engaged and keep talking farmer to farmer.”

Atina Diffley told the keynote audience that the organic movement was about the power of relationships.

“We have to insert organic everywhere,” Diffley said. “We have to be using organic to change the culture. You’re agents of change.”

The organic grower told the group that the movement is about experimenting and sharing.

“It’s not seen in other agriculture or really in America,” Diffley noted.

Diffley went on to talk about the impact of organic agriculture.

“What we are fundamentally doing is changing the culture,” Diffley said. “To think back 30 years ago, we could not imagine this. And, 30 years from now, it’s exciting to think we could be reaching the tipping point.”

Faye Jones, who was instrumental in creating the organic conference 30 years ago, reflected on the conference origins. She recalled Dave Engel was working with OCIA, an organic certifying organization, and wanted to have an organic farmer conference.

Jones described herself as a feisty 20 year old, who raised a fit at the thought of not serving organic food at the conference? Ultimately, she recalled getting organic chicken from the Welsh’s Farm in Iowa to serve at the first organic farming conference.

Soils scientist Frances Thicke said he had been farming organically with his brothers since 1975 and his father didn’t like it.

When Thicke went back to the university to spread the word about the value of organic agriculture and soil fertility, he was met with resistance from his soils professor.

“It depends on how far back to the horse-and-buggy days you want to go,” the professor said of Thicke’s organic notions.

The young, educated farmer went on to work at the USDA for four years, where he never mentioned he was an organic farmer.

“In 2002, I went back to a USDA event and everything had changed,” Thicke said. “Suddenly, it was all about organic, local and on-farm sales.”

When the USDA officials heard about his organic farm, “they loved it,” Thicke recalled.

“I remember the first one we did,” Organic Valley CEO George Siemon said of the original organic farming conference. “Everyone was yearning to share what they’d learned.

“Where will we be in 2049? I’m not sure,” Siemon said. “But, I’m sure that enthusiasm will still be here.”

In their final remarks, the keynote speakers seemed to double down on their optimism about the future of organics.

The MOSES Organic Farmer of the Year, Jim Riddle, noted that organic agriculture embraced research and the future would be based on real knowledge and findings.

“Organic is not about going back to the horse and buggy,” Riddle said. “It’s cutting edge science.”

The Minnesota grower was pleased with the growing new awareness of the importance of soil health.

However, one new twist in organic certification did not please the local farmer.

“It bothers me that soilless hydroponic produce can be certified organic,” Riddle said. “Hydroponic is fine, but it’s not organic and it needs to end.’

As for the conference, Jim Riddle was enthused.

“I came back to be engaged,” he said. “You used to know everybody at the organic farming conference when there were 90 people. It’s much bigger, but I can walk away uplifted and ready to do my part.”

Anita Diffley, another veteran grower from Minnesota, was also pretty positive about organic agriculture’s future and the conference in LaCrosse.

Diffley insisted that organic agriculture is about way more than the USDA organic standards and the market.

“Organic is about a movement,” Diffley said. “The market is the way to reach a point.”

Diffley recounted the organic farm she built with her husband Martin and the end as it was washed over by encroaching development. Anita explained that as every tree, bush and blade of grass was removed from adjoining property, water ran out over the crops.

“We witnessed an ecological collapse,” Diffley said. “We had brought so much more diversity to the landscape.”

The Diffleys have since moved to another organic farm property.

Faye Jones, an organizer of so many of the past organic farming conferences, let her amazement show at what had happened since that weekend conference of 90 people at the Baus Haus 30 years ago.

“I don’t think any of us imagined 30 years ago that there would be 3,000 people at the conference,” Jones said. “Or that the organic industry or movement would be growing to what is has grown.”

Francis Thicke, the organic farmer from before it was called organic agriculture, outlined the need to strengthen the organic standards. Thicke said hydroponic growers lobbied to get organic labeling because they wanted a piece of the pie of what is now a $50 billion industry.

Thicke cited the work of the Real Organic Project in trying to get organic standards back to their original intent.

Thicke said confinement dairy cannot be organic and chickens raised in CAFOs can’t be organic.

“Only a small proportion of organic growers are violating the rules, but they account for a huge portion of the sales,” Thicke noted.

Audrey Arner believes organic agriculture needs to be concerned with water quality and can through its standards and practices.

“That’s our job,” Arner said.

Siemon saw some irony in the increasing role of science in the support of organic agriculture.

“Science is now our friend,” Siemon noted. “It defends the values of organic agriculture. Science has come to our rescue. It’s kind of odd, since we never cared about science that much.

“Organic means taking all the parts to create a whole,” Siemon said. “Organic farmers want to leave the world a better place than they found it. People here have lived it. We need to work with everybody else to make this happen for the future generations.”

Editor’s note: Organic Valley CEO George Siemon resigned from his position as head of the LaFarge-based organic producer co-operative just a few weeks after appearing at the MOSES Organic Farming Conference in LaCrosse. Siemon had served as the CEO of Organic Valley for 30 years.