NOTE: Crawford County will hold a public hearing about the issuance of a Livestock Facility Siting Permit for the Roth Feeder Pigs II hog CAFO facility in Marietta Township on Tuesday, July 12. The hearing is scheduled from 12:30-2:30 p.m. in Suite 236 of the Crawford County Administration Building, 225 N Beaumont, Prairie du Chien Wisconsin.

Written comments will be accepted until 3 p.m. Mon-day July 11, 2022 at the Crawford County Land Conservation Department, Suite 230, Crawford County Administration Building, 225 N Beaumont, Prairie du Chien, WI, 58321.

Virtual attendance will be possible for the first 100 people who register. If at-tending virtually you must register by 12 p.m. on Monday July 11, 2022. To register or to view applica-tion materials online visit our website at www.crawfordcountywi.org/land-conservation-home.htmlDRIFTLESS - Last week, this reporter accompanied a multi-disciplinary group of government officials on a visit to the Iowa Flood Center in Iowa City. In addition to flooding, the Center also has a focus on water quality, and measures phosphorous and nitrate pollution in Iowa’s drinking water.

The group from Wisconsin included Monroe County Administrator Tina Osterberg; Wisconsin Emergency Management West Central Regional Director Lisa Olson-McDonald; U.S. Fish & Wildlife Fish Habitat Biologist and Fishers & Farmers Partnership Coordinator Heidi Keuler; Wisconsin DNR’s Cindy Koperski; Wisconsin Land+Water’s Christina Anderson; Monroe County Emergency Management Director Jared Tessman; Monroe County Conservationist Bob Micheel; and Monroe County Land Use Planner Roxie Anderson.

Chris Jones is a research engineer with the Iowa Water Quality Management Initiative, which is housed under the Iowa Flood Center umbrella. He was formerly a member of the Iowa Soybean Council and also sat on the board of the Fishers & Farmers Partnership. Jones manages the University of Iowa’s network of water quality sensors.

With two field staff, Jones manages 70 water-quality monitoring sites throughout the state. The effort is funded through part of a tax on fertilizer sales in the state. Almost real time results of their monitoring can be found on the ‘Iowa Water Quality Information System’ website at https://iwqis.iowawis.org.

Jones said that there are 8,000 Confined Animal Feeding Operations (CAFO) in the state. These operations house 25 million hogs, four million beef cattle, 80 million laying chickens, five million turkeys, four million broiler chickens and 220,000 dairy cows.

“Total Iowa fecal waste generated from CAFOs is the equivalent of 170 million people,” Jones explained. “The human population of Iowa is three million people.”

He described land use in the state, which has led to the state’s ground and drinking water crisis. Corn and soybeans cover 70 percent of Iowa land, and agriculture uses 85 percent of the land. Streams have been straightened, with eroded banks and a heavy sediment load from soil erosion, and fields have been extensively tiled to facilitate spring planting.

“Wetlands used to cover 20 percent of Iowa or 7.6 million acres, and now less than one percent remains. Oak savannah used to cover five percent of Iowa, and now less than one percent remains,” Jones said. “Prairie was the dominant land cover prior to settlement, covering 70 percent of Iowa, and now only 0.1 percent remains.”

Jones said the consequences for the State of Iowa of these land uses is massive soil erosion, and nutrient pollution of ground and surface waters.

“In Iowa, 7,000 private wells have tested above the safe drinking water level for nitrate of 10 milligrams-per-liter (mg/L) since the year 2000, and one third of Iowa’s Public Water Supplies are vulnerable to nitrate contamination,” Jones said. “Sixty public water systems are forced to filter out nitrate, with 25 percent of Iowa’s drinking water being treated for nitrate reduction.”

In the Missouri River basin, in western Iowa, the state contains 3.3 percent of the land in the basin and 12 percent of the water, but contributes 55 percent of the nitrate.

In the Upper Mississippi River basin, Iowa contains 21 percent of the land and water, but contributes 45 percent of the nitrate.

In the entire Mississippi River Basin, down to the Gulf of Mexico at Atchafalaya, Iowa contains 4.5 percent of the land and 5.9 percent of the water, but contributes 29 percent of the nitrate.

Regarding phosphorous, the State of Iowa contributes 15 percent of the phosphorous load to the Gulf of Mexico, and represents 4.5 percent of the total drainage area.

“Phosphorous concentrations in Iowa streams are likely two-to-three times higher than in Illinois streams on average,” Jones said. “The phosphorous loads in Iowa streams are 43 percent higher in 2017 than they were in 2004.”

All of this has come as Iowa, like Wisconsin, has become hotter and wetter. Like Wisconsin, the greatest change in temperatures have occurred in winter. In 1893, the average annual inches of precipitation was just under 30 inches, and in 2019 it has become about 48 inches. The greatest increases in annual average precipitation have occurred in the north central, northeast and east central regions of the state.

This additional moisture has led to a dramatic increase in tiling of fields. This is done to drain the fields in the spring so that timely planting of row crops can be achieved.

For example, Jones says that about 1,200 miles of new tile is being laid every year in Iowa’s Middle Cedar River Watershed. This amounts to about 4,364 acres per year. In 2018, Jones said nitrogen loss was about 31.5 pounds-per-acre (lbs./ac.). New tile being laid, he said, will multiply the nitrogen loss one-and-one-half times or increase the nitrogen loss by 15.9 lbs./ac. This results in an increases in the nitrogen load in the watershed of 69,000 lbs. per year.

Jones said that the citizens of Iowa support funding to help address these water quality issues, but that the Iowa State Legislature has refused to act. He said that in 2010, 62 percent of voters recommended enactment of an ‘Iowa Water and Land Legacy Act,’ which would fund water quality improvement efforts through a small percentage of sales tax revenue, but the legislature has never taken action on that recommendation of the state’s voters.

SWIGG in Iowa

Next up was Iowa State Geologist Keith Schilling. Schilling heads up the Iowa Geological Survey, which has been moved to live under the Iowa Flood Center and the Iowa Hydroscience and Engineering Department umbrella.

Schilling described his department’s efforts to conduct a Karst Susceptibility and Sinkhole mapping project for the state, which he described as a ‘gamechanger’ in understanding the state’s water quality problems.

“What we found is that the primary factors in development of karst geologic features, such as sinkholes, is the depth of soil to bedrock, and the type of rock that forms the bedrock,” Schilling explained. “We found that 85 percent of sinkholes in Iowa are found in areas with less than 25 feet of soil to bedrock.

Schilling said he had become inspired when he saw the final results of the ‘Southwest Wisconsin Groundwater and Geology’ study (SWIGG), and asked himself, “why aren’t we doing that in Iowa?”

In Iowa, every landowner can request one free well test per year. Those free tests will test well water for unsafe levels of nitrate, coliform bacteria and E.coli.

“Once we launched this effort, our first key task was to assign every well for which we had a result to a groundwater aquifer,” Schilling said. “We have construction reports for 20 percent of the wells, and are busy compiling all the same sort of information used in the SWIGG Study, except for the microbial source testing, and hope to publish a similar study.”

Schilling said that through his department’s work, they have established that there is no question that proximity of a well to a sinkhole formation influences nitrate levels in water in most aquifers. He said that the problems are most acute in the north central, northeast and east central parts of the state, which have a karst geology similar to that of northeast Wisconsin (Kewaunee County).

He said that, unlike in Vernon and Crawford counties, the aquifers in those regions of Iowa are located in a very shallow layer in the bedrock formation. This means that it can become very contaminated, very quickly, and can also flush relatively quickly. By contrast, the aquifers in Crawford and Vernon counties are located in a very deep sandstone layer in the bedrock profile, where water infiltrates more slowly but is also much slower to flush.

Watershed Commissions

Larry Weber, who served as the first director of the Iowa Flood Center after its formation in 2009, now serves as the project lead for the ‘Iowa Watershed Approach’ initiative. He said that an act of the Iowa Legislature in 2010 established the authority of municipalities to work across political subdivisions on a watershed scale.

“So, in Iowa, instead of having County Land Conservation Departments like Wisconsin does, we have watershed commissions,” Weber explained. “The members of a watershed commission are elected to their positions.”

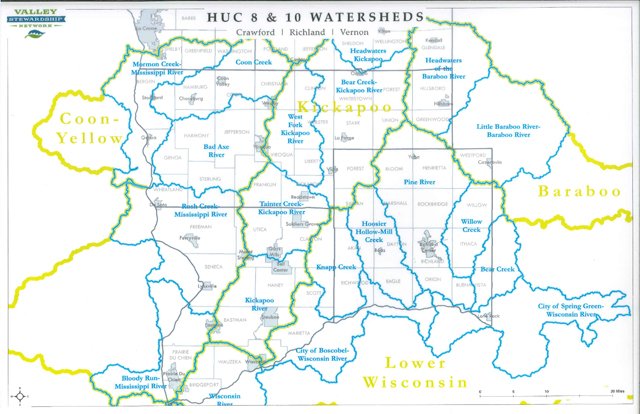

Weber said that these commissions, of which there are currently 56 in Iowa, are assigned to watersheds no larger than a HUC-8. The ‘HUC-8’ designation comes from the U.S. Geological Survey, and maps the sub-basin level, analogous to medium-sized river basins (about 2,200 nationwide, with HUC 12 being a more local sub-watershed level that captures tributary systems (about 90,000 nationwide).

“The approach was stimulated by a successful pilot conducted in the Soap Creek Watershed, starting in 1986,” Weber said. “In that pilot project, formed with approval from the county board, hundreds of farm ponds were constructed, increasing water storage in the watershed, and the payoff was in the form of lower cost replacements for stream crossings in the watershed.”

Weber said that the data that had come out of this pilot project, with structures that have now been in place for over thirty years, was invaluable in creating their application to the legislature for the formation of the Iowa Flood Center and the Iowa Watershed Approach.