Part two: During the spring and summer of 1924, Ku Klux Klan organizers met in Muscoda in preparation for a rally in Boscobel. Boscobel was both a largely Catholic municipality and the birthplace of KKK opponent and then-Governor John J. Blaine. The rally was part of the KKK effort to campaign against Blaine, who was up for re-election, and a showing of strength, and in the opinion of some, of defiance. Blaine had successfully stopped the group from rallying on state property on the basis of masks being used to hide the identity of participants.

Throughout the spring and early summer of 1924, the Boscobel Dial maintained silence about the activities of the Ku Klux Klan in neighboring Muscoda. As the date of the Klan rally planned in Boscobel approached and passed, the newspaper had nothing to say.

That was about to change, as was the tenor of coverage in the Muscoda Progressive regarding Klan activities. Both municipalities were to soon have legal cases pending. Each covered their respective case in a very circumspect manner, as they involved community members.

Boscobel rally

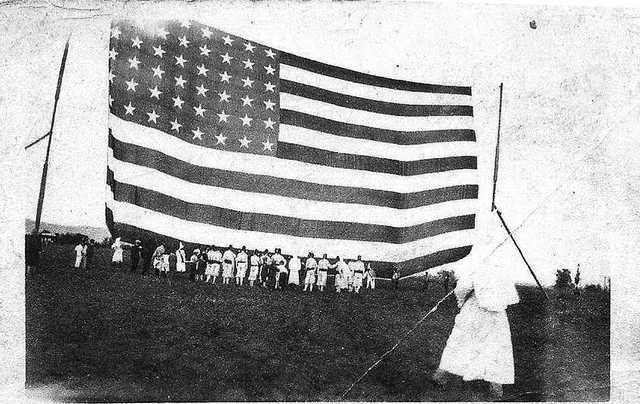

On August 16, 1924, approximately 200 Klansmen from several counties gathered at Rick’s Field just west of Boscobel for an all day and evening rally, complete with parade.

The event, which ended with a cross burning, reportedly drew some 7,000 spectators, according to the Lancaster Herald.

While the rally apparently went well, the parade was another matter.

Accounts given many years later stated that night policeman George Shields had promised citizens in town that he would stop the parade on the grounds that it was illegal.

Ninety-eight robed men proceeded from Rick’s field into town for the parade.

“When the parade came to his position, he stepped into the street and pulled the mask from the leader, and as he moved to the next man, he was struck to the pavement,” according to witness Earl Williams, of Boscobel, as recorded in 1968. “As Shields jumped to his feet, he pulled the trigger on his assailant, but the gun failed to fire. Other police officers apprehended the two men and took them to the county jail.”

A second attempt was made to block the parade by an unnamed person or persons. A car drove across the path of the parade, but marchers pushed it out of the way.

Investigation requested

A few days later, on August 19, H.E. Austin of Boscobel wrote to the Governor’s office asking the governor to urge the District Attorney to investigate the matter, stating that Shields “was assaulted and hit over the head with a Billy or its equivalent by one of the masked Ku Klux Klan” during the parade down Main Street.

Blaine’s secretary, Frank Kuehl, forwarded the request to Grant County District Attorney George B. Clementson. Blaine was campaigning outside of Madison at the time.

The request did not have the expected results, prompting the Governor to send a telegram on August 22, ordering the investigation and/or arrest of the Klansmen involved in the incident.

Clementson chose to arrest Officer Shields instead.

Blaine sent another telegram, telling Clementson his decision “put the cart before the horse.”

“The circumstances involved more than a local officer and the whole state is interested in preventing mob rule superseding government,” Blaine stated.

Clementson held fast to his decision to charge Shields as the aggressor.

But the flames were about to be fanned in another incident of violence.

Twenty-five year old Leo Manning of Muscoda was shot with buckshot during a reported altercation with the Ku Klux Klan on September 3. A Klan rally was planned in Muscoda that day and Manning was accused of attempting to set fire to a building used by the Klan to organize.

“This is the second time an attempt has been made to burn down the Klan building,” Muscoda police chief Briggs told the Wisconsin State Journal. “The first time the incendiaries set fire to the building, but the flames were put out before much damage had been done. This time they had brought a can of kerosene with them to make sure of the job, but the shooting occurred before they had time to get it off.”

Manning, a Catholic, was only one of many who had come to town in opposition to the parade planned in Muscoda. The parade never materialized, apparently called off in light of possible conflict.

“This is a Catholic community and a Klan demonstration in this town would be an affront to the majority of the citizens,” an anti-Klansman had told a reporter. “We are not going to allow it. We don’t intend to have a repetition of the Boscobel fracas.”

Grant County Sheriff J.H. Edge arrested Muscoda store owner Frank Groves on a warrant arising from a John Doe investigation begun the day of the shooting by Clementson.

Suspended

In the meantime, citing Clementson’s failure to arrest Klansmen in the Boscobel case, Blaine suspended the Grant County prosecutor.

“Your attitude as evidenced by your telegram to me of Aug. 23 tends to encourage and give aid and comfort to that organization and tends to engender bloodshed such as occurred. In the last 48 hours at Muscoda. Wis.,” Blaine wrote Clementson regarding his suspension. “Moreover, your attempt to give the governor's directions a partisan and political appearance is quite contrary to your obligations as an officer whose duty it is to prosecute. The Klan demonstration at Boscobel on Aug. 16 was menacing. It produced a state of fear and terror among the citizens of that community.”

Both Shield’s and Grove’s cases would be heard by Grant County Judge E. B. Goodsell in Lancaster.

Clementson’s suspension was lifted by the time the cases went to trial shortly after, following a campaign by Clementson in the state newspapers to vindicate his stance. He claimed his suspension was political and not substantiated on the case, arguing that he had followed the letter of the law. The proof of violence on the part of the Klan was not substantiated in the Shields case. And in Manning’s shooting, an arrest had been made.

Initial hearings

“I have heard statements that participants in the Klan parade were armed. ” Clementson argued in Shield’s trial. “I can uncover no evidence to that effect. If Shields' gun had gone off… (in the face of B.A. Flesch of Muscoda)…we should have found out if any were armed.”

“Interesting climaxes occurred on two other occasions, once when a woman witness showed apparent uncertainty as to whether she should place her oath to the Klan above her duty as a witness and again when three bystanders in the Boscobel affair declared, contrary to testimony of several paraders, that they had seen no gun in Shields’ hand until after he had been struck by Flesch.”

Both Shields and Grove were bound over for trial in October, though it was Shields who maintained the attention of the newspapers statewide.

An outbreak of diphtheria in Muscoda affected many witnesses in Grove’s case, resulting in the case being delayed until February 1925. The delay pushed the Grove case from the public mind causing it to effectively disappear.

One day trial

The Shield trial lasted one day. Deliberation of an hour and a half the following day returned a verdict of guilty, which he appealed. Sent through the appeals process, Shields’ case eventually made its way to the Wisconsin State Supreme Court in April 1925. The Supreme Court upheld Shields conviction in April 1925, sentencing him to a year in jail.

The political nature of the case was retained to the very end. Governor John J. Blaine gave Shields a full pardon in October 1925.

“With my knowledge of the history of the Klan, its teaching of hatred, its production of bloodshed and murder, I will not discourage the peace officers of this state in preserving the traditional history of our state for law and order," Gov. Blaine declared. The governor declared that petitions for Shields' pardon had been made by the present mayor of Boscobel, the city clerk, city attorney, city marshal, six of the present aldermen, three ex-mayors and "substantially all of the businessmen of Boscobel and he has been reinstated as night policeman” and “with increased salary.”

An observer for the Wisconsin State Journal noted that the antagonism between Klansmen and anti-Klan witnesses and observers was a palpable presence throughout the legal proceedings in Shields’ case, a presence thinly masked by politeness and social conventions.

A waning force

Despite being able to attract large numbers of onlookers to their various sponsored events in Grant County and elsewhere in southern Wisconsin, the Ku Klux Klan was on the wane by 1925. A repeated narrative in accounts of rallies was large numbers of people showing up early and then quietly packing up and leaving as vitriolic speeches on race, religion, and the definition of what constituted being a “real” American were made.

In November 1924, Grant County elected E.I. Rothe, an opponent of the Klan, to the State Senate. The same election saw Blaine, a member of the Progressive caucus in the Republican party, re-elected to the Governorship.

The lines drawn between Progressive politics and the Klan were probably the only clear line drawn in the ambiguous response to change that spawned both movements.

As the Klan argued for segregation, traditional roles, and disempowerment of non-Protestant religions, Progressive Republicans were seeking changes of their own - limiting child labor, reinforcing local control (“home rule”), fighting the concentration of wealth in the hands of a small few, enacting conservation of natural resources for current and future generations – all while opposing the Klan as an emblem of hate and division.

The fight clearly forced to the forefront a discussion of both American ideals and constitutional protections.

The KKK fell apart under the weight of its own organizational struggles and a Wisconsin public that increasing asked what the money it was raising was used for. Compiled small scandals tarnished its reputation. After the mid-1920s, it never regained the political sway that it built in the years immediately after WWI.

Within a few more years, the stock market crash of 1929 and the following decade of the Great Depression left it clear for everyone that, to use the words of my grandmother, Grace, who grew up during those difficult times, “Folks are folks and we are all in it together.”